The modern world lives on electricity; we cannot sustain the standard of living we enjoy today without it. Electricity keeps us warm; it ensures our food is preserved, that we can have a hot meal, and remain clean and hygienic, and it provides us with protection against weather conditions. It provides us with the means to communicate and access information and entertainment.

Having no electricity sets us back as a species, and living without it, impacts our quality of life.

As I write this article, I know full well I will be disrupted within the next 3 hours with my share of load shedding for the day, having to prepare my food, charge my phone and ensure my solar lights are charged for this game of musical chairs for access to energy.

These daily disruptions are not only an annoyance for the average citizen, but they impact business operations too. The lack of electricity means we have fewer hours of productivity, which leads to job loss and shortages of products in supply chains.

Having limited capacity means producers have to increase their prices as they produce less pushing up producer price inflation, which later transfers over to the citizen in consumer price inflation and impacts our overall standard of living.

What is load-shedding?

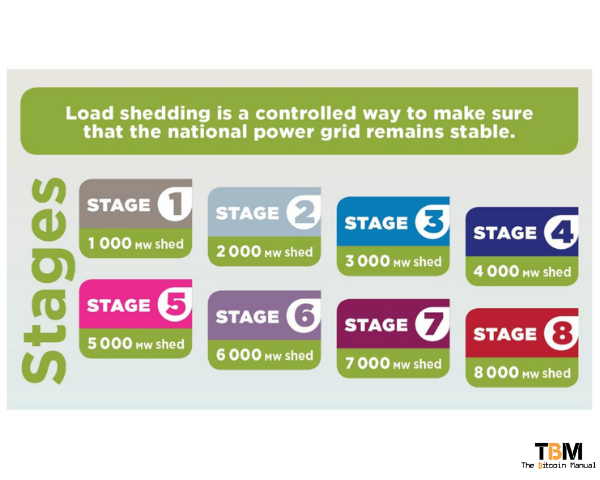

For those of you who are not South African or in a country that doesn’t have to deal with intermitted access to electricity, load shedding is a systematic shut down of access to electricity. When the national and multiple providers cannot meet the daily demand for electricity, certain regions of the country are shut down for 1 – 2 hours to reduce the load.

As the energy capacity of the national grid continues to fall short, these bouts of load shedding continue to increase, from 1 hour to as high as 6 hours per day.

If load shedding is required, Eskom, the country’s National provider, and grid control center, instructs its stakeholders (i.e. the municipalities and customers to whom it sells electricity to reduce the capacity by a certain amount of megawatts. Each reduction is categorised into stages of load shedding. The duration of load shedding will depend on the specific supplier (Eskom or municipality), region and circumstances, and stage you’re on at the time.

What is the cause of load-shedding?

Load shedding, or the South African Energy Crisis, began in the later months of 2007 and continues to this day; some years have been better than others. South Africans have had this monkey on our back for 15 years, but it was not something that came out of the left field. In a December 1998 report, analysts and leaders in Eskom and in the South African government predicted that Eskom would run out of electrical power reserves by 2007 unless action was taken to prevent it.

Increased demand

As South Africa became a unified country with the fall of apartheid, informal settlements turned into bustling suburbs, and informal businesses turned into an industry. As more people began to participate in the economy and earn a better living, their energy demands increased.

Deterioration of current supply

South Africa’s energy needs continued to grow, but its grid and infrastructure were not well maintained.

The current bout of load shedding is related to inadequate national energy supply to meet demand. This is mainly due to a large amount of unplanned maintenance required at Eskom’s aging coal-fired power stations.

Lack of new supply

In addition, the new power supply did not come online as predicted, leaving the country with massive shortfalls. The new energy generation units at Medupi and Kusile have faced challenges in bringing the units online.

South Africa’s nationalisation of energy production and its reluctance to allow private producers to come in and augment the supply meant that it would always turn out to be a central point of failure.

Sabotage and corruption

Despite these apparent forces putting a chokepoint on access to more energy and, more importantly, cheaper energy production, we also saw self-inflicted wounds on an already strained system. Power stations and power production supply chains have been deliberately attacked while certain suppliers who tendered for contracts failed to live up to their agreements leaving the country high and dry while individuals profited from these dealings.

Illegal connections

Electricity theft in South Africa is systematic and widespread; according to Business Tech, in 2015, 32% of Johannesburg’s energy was never compensated. These trends continue to grow around the country despite the various cities’ best efforts to curb the practice.

As electricity becomes more expensive due to the lack of supply, it only further encourages the practice of stealing from the grid and not compensating energy producers. This leaves the remaining paying customers to pick up the shortfall through higher prices, and while it may benefit those that steal in the short term.

In the long term, it makes all of us poorer as higher costs for energy lead to disruption in supply chains, and the costs also get passed on to consumers through higher prices for goods and services.

What is South Africa’s energy mix?

The South African energy supply is predominantly run by coal which constitutes 69% of the primary energy supply, followed by crude oil with 14% and renewables with 11%. Nuclear contributed 3%, while natural gas contributed 3% to the total primary collection as of 2016.

South Africa’s Energy mix potential

South Africa does not have a power shortage due to a lack of potential sources, that’s for sure. Frankly, the country has an embarrassment of riches with the potential ability to tap into seven different energy sources creating a robust energy mix for years to come.

It’s more a case of making it economically feasible to bring these energy sources online and get them up and running at full capacity, which takes time and of course money.

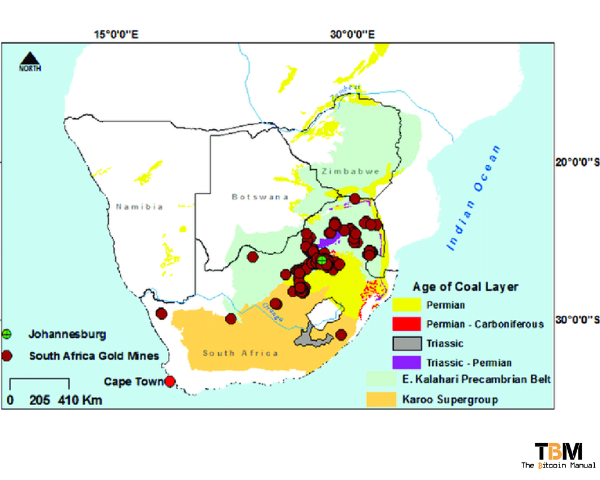

Coal

According to worldometers.info South Africa holds 35,053 million tons (MMst) of proven coal reserves as of 2016, ranking 8th in the world and accounting for about 3% of the world’s total coal reserves of 1,139,471 million tons (MMst). South Africa has proven reserves equivalent to 173.3 times its annual consumption.

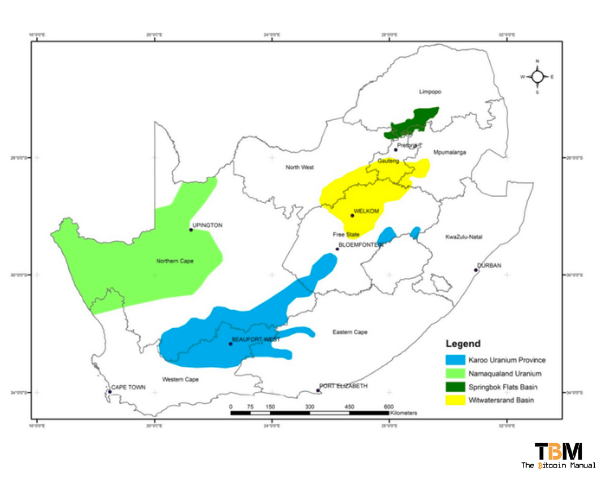

Uranium

According to miningweekly.com South Africa is among the top countries in the world with uranium reserves, and accounted for a significant reserve base of an estimated 433 364 t of uranium, or around 7% of global proven reserves in 2010. The country contributes over 45% of total African uranium reserves.

Thorium

If we consider the more experimental side of energy production with the likes of alternative nuclear energy then we’re up there with the best in the world. South Africa has the fifth largest deposit of thorium in the world thanks to the world’s richest thorium mine, Steenkampskraal, in the Western Cape, about 350km north of Cape Town as reported by iol.co.za.

Hydro

Hydro is currently only 2% of South Africa’s energy production with 3,586 MW of hydropower including 2,832 MW of pumped storage capacity producing some 4,750 GWh of electrical energy per year, but we have not fully capitalised on this energy source. Estimates from andritz.com claim that it is technically feasible for the hydropower potential of South Africa to generate around about 14,000 GWh/year, of which about 90% has already been developed.

While only tripling the capacity of what we currently generate, when you can produce energy at capacity you also allow for offsetting from other sources for an overall reduction in cost.

It’s also worth noting that these are only estimates based on current infrastructure, that is not to say more hydro plants of a smaller size cannot be brought online if there are energy consumers willing to pay for it, which could bring further production of clean energy online with reports by wrc.org.za claiming that up to 17 500 GWh/year could be brought online through small hydro plants.

Solar

We’re not known as sunny South Africa for nothing, most of the country remains warm and toasty all year with areas in South Africa averaging more than 2 500 hours of sunshine per year, and average solar-radiation levels range between 4.5 and 6.5kWh/m2 in one day.

The southern African region, and in fact the whole of Africa, has sunshine all year round. The annual 24-hour global solar radiation average is about 220 W/m2 for South Africa, compared with about 150 W/m2 for parts of the USA, and about 100 W/m2 for Europe and the United Kingdom.

This makes South Africa’s local resources one of the highest in the world as reported by energy.gov.za

Wind

According to sawea.org.za the current capacity for wind in the country is 3024MW while the total wind power potential of South Africa is estimated to be 6,7000 GW.

While both solar and wind pale in comparison to the likes of nuclear and coal and have limits to their energy density, they are still options to be explored but may not make much financial sense if the more energy-dense options are brought on at any real scale.

They may be helpful for residential use which means more resources are available to push towards our manufacturing base, reducing costs of production reducing our cost to access locally produced goods, and making our exports even more competitive.

Energy has start-up costs

Power plants and their supply chains are not built overnight, they require massive investments, investments that need to be recouped, usually in the price of the commodity they produce, so even if we bring more energy online, there is no guarantee that it would bring down the price of energy.

How bitcoin mining helps current energy production?

Now that we’ve established the current issues, potential capacity, and the gap between the current reality and possible energy-abundant reality, how do we get there? My idea would be to leverage the power of bitcoin mining and its incentive structures to bootstrap and compensate energy producers.

When energy is produced, be it hydro, coal, or nuclear, the result is the turning of a turbine to generate the electricity; once electricity is generated, it is then transported to a place to be used; if not, it is lost. The reality is the same for all electricity generation but even more so for the likes of renewables which require a certain optimum condition to operate and are less energy-dense.

Balancing energy capacity

Balancing energy loads are important to get the most out of your resources, and energy producers are constantly monitoring demand to try and produce the most electricity with the least amount of waste. You don’t want to be running your operations at 90% capacity when you only need 65%.

This constant changing of capacity puts strain on maintenance and means we produce inefficient energy loads with a lot of “spillage”, meaning we have to pay more for the energy we do get, as we’re not maximising our resources through economies of scale.

Instead of constantly shifting your energy capacity, having bitcoin miners attached to your operation provides a battery of sorts. You can run your operation at maximum capacity with any excess energy gobbled up by miners. Alternatively, when energy is abundant, miners can continue to provide a floor price for that energy and compensate energy producers.

This means there is a constant flow of income and when consumers require the energy, you need not charge them as much for their needs. In having this symbiotic relationship, miners monetise energy assets that would otherwise be dumped into the ground while maintaining generally high uptime.

Efficient energy transport

Another issue comes in energy transportation; the further energy needs to move from the point of production to the point of use; the more is lost in the process.

Bitcoin mining can be used to maximise lost energy in certain regions; perhaps a wind or solar farm produces enough energy to keep a small town off the grid, but excess capacity is wasted instead of letting it go to waste or expending resources to try and transport that energy via the grid, it can be used in the local area to mine bitcoin.

Again in the previous case, the miners compensate the energy producers and ensure that the local area production is more efficient and cheaper. The cheaper the energy is, the more the local economy can use it to produce goods and services, making business operations more feasible.

South Africa has several stranded energy sources in the form of wind, solar, and small-scale hydro, and there is no reason why small-scale nuclear cannot be added to the mix. Having bitcoin as the backbone for standard energy means we also decentralised the energy grid and the reliance on one producer for all our needs.

Instead of the primary grid having to transport energy nationwide and losing energy in the process, we now encourage local economies to become self-sufficient.

How does bitcoin mining help bring more energy online?

When it comes to energy production, bitcoin is a pioneer species, as quoted by Brandon Quittem. Bitcoin miners are actively looking for the cheapest energy available so that they can maximise profits; bitcoin miners will happily set up where others won’t as long as the energy is available cheap, abundant and has low competition.

When these three things are true, it reduces the time to profitability and makes it worthwhile to sink in upfront cost to set up a new mining operation, migrate an old operation or scale down one operation to scale up to another.

Bitcoin is the sugar daddy of energy producers; it’s willing to throw cash at anyone willing to take the risk of finding, securing and setting up an energy-producing asset. Energy sources that may not have been feasible in the past now make economic sense, and as new energy assets are set up, they have a buyer.

The moment you bring that energy source online, you can start mining bitcoin and generating an income; as that income bootstraps the new energy production and has free reign on the resources, eventually, that energy asset will attract other buyers, it could be industry, agriculture or it could be residential.

Bitcoin allows for those energy seeds to mature and, once sprouted, will compete for the energy available until they are bid out of the market or scaled to the point of equilibrium with that market while other miners move on to pioneer new sources of energy for profit.

How bitcoin mining reduces energy costs

When you mine for bitcoin, you’re rewarded with a commodity, the hardest money the world has ever seen. Money with international demand and growing pools of liquidity that you can access.

Bitcoin trades 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, so there is no shortage of access. Miners can produce a monetary good that has global demand meaning they can acquire capital by liquidating their bitcoin at any time to cover costs of operations and pay for energy.

If the bitcoin treasury is managed, miners can pocket a healthy profit either by leveraging the bitcoin or hash rate to take on fiat denominated debt which they pay off over time or by selling bitcoin during market rallies to increase their operating cost runway. Since these bitcoin operations have access to liquidity in various forms, they remain indiscriminate buyers of electricity and pay for the resources they use, compensating producers at a market rate.

When energy use is high, bitcoin miners will not want to keep mining in unprofitable times or regions, so they either migrate or lower their demand. As energy producers receive a constant income during periods of low demand and have a price floor that is bid up by consumers when they need it, the producers can have a more reliable income and make better decisions based on these cash flows.

They can offset certain costs based on running at full capacity and maintaining a scale, and with operations running smoother, less maintenance and less downtime, energy prices have a tendency to drop over time.

Reducing the incentive to steal

As bitcoin mining continues to offset the costs for consumers and the price to access energy on demand reduces, it also reduces the incentive to steal electricity. The costs become so negligible that having an illegal connection loses its appeal, and with that, you bring more paying customers into the ecosystem.

The more paying customers who feel they are getting a good deal, the higher the stream of constant capital moving into energy producers’ treasuries to be used to maintain their operations or use it to explore new energy sources.

There will always be those wanting to steal or get something for free, but a reduction in the number of people operating illegally makes law enforcement and management of reducing illegal connections cheaper and more efficient to carry out.

Transparency of funds

If South Africa had a nationalised bitcoin mining operation, the whitelisted public key addresses where funds are deposited from mining could be tracked by anyone with a bitcoin node or access to a block explorer. It’s easy to create a bot that monitors the address and tweets every time funds are deposited or moved from the bitcoin address.

This provides oversight on the funds produced from our “unused” national energy production, and with so many eyes on those addresses, the slight movement of funds would trigger questions. Citizens can demand to know where those funds are going and have access to the data and the value at the time funds were moved, so there is little place to hide.

Adding custodial responsibility of funds

The addresses that hold the bitcoin mining could be held in a multi-sig address, for example, a 3 of 5 or 6 of 10 set up. This means that three people or institutions holding 1 of the keys would need to collude and sign to move those funds. As long as a majority agrees, the funds can be moved.

As long as the people and institutions holding one key are made public, we would know who is responsible for moving the funds, and even if one or two keys are compromised, the funds remain safe.

Returning stolen funds

Since we all know the public addresses used and the UTXOs held in that address, even if key custodians have been corrupted or colluded into moving the funds. The UTXOs could be blacklisted (added to a watch list), and if they do hit an exchange or a wallet where the user can be identified, these funds can be seized.

The advantages of mining scalability

Bitcoin mining is incredibly scalable; it can be as small as one ASIC miner to as large as an entire data centre, which can be scaled to support any energy source. The fact that it can be scaled up or down means miners can also be moved to energy sources where it’s more economical to mine, so resources are not going to waste.

Miners follow their economic incentive to find the cheapest electricity and, in turn, provide energy producers with an income that matches their excess capacity.

There is no utopia

I’ve laid out my case for how bitcoin could help the problems we face in the country, but I am under no illusion that bitcoin mining would be a silver bullet. We would have to overcome political and business interests that benefit from the current situation; we would have to deal with crime and sabotage, which are evident in everyday life in South Africa.

Bitcoin cannot fix these issues once they are engrained in a society, and it cannot protect itself against these forces of societal decay either. Bitcoin can only provide an economic incentive to do what benefits the larger society, but that doesn’t mean people will accept it.

If there’s anything I’ve learned about society, we can remain irrational for a very long time, and in that time, we’re willing to accept and justify self-inflicted wounds. Bitcoin is merely a tool for us to use, and like any tool, we can use it constructively; we can choose to ignore it, or we can misuse it.

Give us your take

So South Africa, what do you think? Could bitcoin mining provide us with a possible solution to our days in the dark? Let us know in the comments down below