Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) — previously known as Miner Extractable Value, has become a thorn in many a smart contract chains side. MEV used to refer to miner-extracted value as mining used to be the primary method of organising blocks on proof of work chains. That has since changed with the introduction of various forms of proof of stake chains removing the need for mining from their consensus protocols.

As the name suggests, Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) refers to securing the maximum value a blockchain miner or validator can make by including, excluding, or changing the order of transactions during the block production process. Miners or block signers are always going to look for ways to improve their returns by hook or by crook since that’s their business.

Miners or block signers commit capital and either into resources like energy and hardware, or they’re risking capital by staking and running complimentary hardware to support the network in question. They’ve taken a risk, and they’re looking to get a reward for that risk and capital tied up in a specific ecosystem.

As a miner or block signer, you could get paid only by the protocol’s standard incentive structure, like block subsidies or block rewards made up of transaction fees, or you could look at adding additional strategies to squeeze out a little more juice.

MEV occurs when the block producers in a blockchain extract value by arbitrarily reordering, including, or excluding transactions within a block, often to the harm of users and is referred to as a “hidden tax” on ordinary users. Block producers can determine the order in which transactions are processed on the blockchain and exploit that power to their advantage.

MEV starts to pick up the pace

The concept of MEV has been around since as early as 2013; with talk about collision attacks or a hash collision on the Bitcoin blockchain, which occurs when two inputs are found producing the identical hash value, thus threatening the security of the cryptographic hash function.

But it was not until 2020 that it started gaining real traction, with most of the action taking place on Ethereum, due to the explosion of tokens, on-chain exchanges, and lending protocols, all allowing for more complex transactions to take place using a host of third-party assets.

MEV has become an increasingly relevant topic due to the growing popularity of decentralised finance platforms and their critical role in enabling complex financial transactions within the wider blockchain ecosystem since every chain since Ethereum has looked to copy this Turing complete model where everything is executed on-chain.

As the volume and complexity of transactions on DeFi platforms have increased, so too has the potential to be exploited by malicious or opportunistic actors.

MEV opportunities exist due to the way blockchains work; when a user submits a transaction, there is inherent latency and competition for block space. If you submit transaction nodes across the network, add them to the mempool, and from there; miners would select the transactions they want to add to a block.

If you’re only considering the native asset as your method of profit calculation, you will construct your blocks with the transactions that pay you the highest fees and can fit into the limited block space provided.

In an MEV world, the value is derived from manipulating the transaction order in a block which includes inserting or censoring certain transactions.

On chains where MEV is rife, MEV bots monitor the pending transaction queue to identify opportunities to generate MEV revenue. In instances where they successfully identify an opportunity, they are programmed to automatically submit transactions on behalf of their operators to capture MEV rewards.

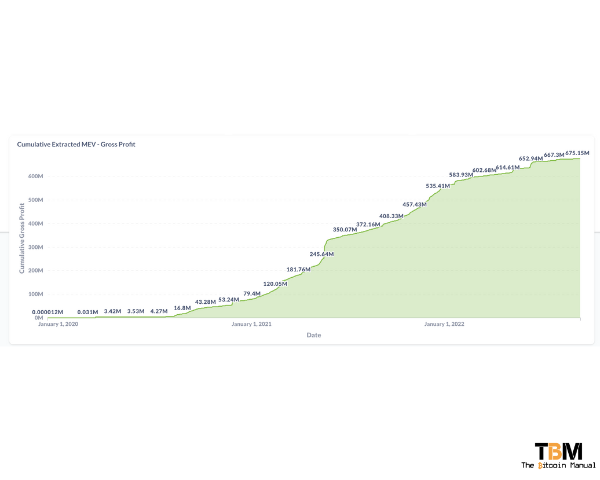

This has become a rather lucrative practice on chains like Ethereum, with reported MEV revenues reaching well over 600 million USD.

Types of MEV

MEV comes in a host of shapes and forms, but the most popular tactics include:

DEX arbitrage

On-chain exchanges list different prices for the same tokens as a result of different levels of demand and liquidity or order books. If a wide price discrepancy appears on one exchange versus another, it presents an opportunity for MEV extraction.

MEV Bots aim to find these price mismatches and exploit these situations by buying tokens at a lower price at one exchange, turning around and selling them on a second exchange at a higher rate in the space of a few blocks.

Arbitrage, in this way, is still extractive to those involved, but it does provide a more efficient market for traders.

Liquidation

In a DeFi lending space, users must deposit their assets as collateral. If a user isn’t able to repay their loans, the protocols often allow other participants the chance to liquidate the collateral and gain a liquidation fee from the borrower. Again MEV bots watch out for these opportunities to find borrowers primed for liquidation to gain the liquidation fee for themselves.

Arbitrage and liquidation can benefit the market, with arbitrage leading to more efficient pricing and fast liquidations necessary to ensure lenders recoup their money.

While this liquidation practice is not frowned upon, it can become malicious if exchanges or large market markers push certain assets into liquidation to feed their MEV bot positions. A situation that is easily achieved with thinly traded altcoins that require very little capital to move markets.

Front-running

MEV front-runner bots can search the mempool for transactions that could be profitable by purchasing or selling a specific asset. Upon discovering a qualifying transaction, the bot replicates the original transaction but with a higher gas price, prompting miners to choose that transaction over the first one.

This way, the front runner can benefit from the price increase or decrease driven by the larger order they spotted in the mempool.

Sandwich attack

A so-called “sandwich attack” is a technique used to manipulate the prices of a specific token for a short period. An MEV bot will seek out a large trade pending on a DEX and attempt to “sandwich” that trade between their own.

The searcher places a trade using the same token immediately before and another right after the sizeable pending trade to benefit from the temporary (and artificial) price discrepancy.

Ordinals bring MEV to Bitcoin.

In practice, however, MEV has rarely appeared on Bitcoin since the majority of Bitcoin transactions are “simple” transactions transferring UTXOs between two parties. Since more complex transactions are required for MEV to flourish, Bitcoin really hasn’t been an attractive place for these tactics.

However, that has begun to change with ordinal theory creating secondary markets such as NFTs, BRC-20 Tokens, STAMPS and Rare Sats. As the metadata trading these tokens or “assets” needs to be broadcast on-chain to transfer them between users, list them on exchanges or mint them, they provide opportunities for miners to exploit it.

If you’re not a fan of these speculative markets, then you should welcome MEV, as it places an additional tax on users who want to perform these types of transactions.

Additionally, if efforts to bring more complex transactions to Bitcoin through Taproot Assets or Layer 2 solutions prove successful, the amount of MEV opportunities on Bitcoin could also increase as miners try to front-run capital moving between layers or when secondary assets are involved. Secondary asset markets could also be built on client-side protocols like RGB, which might not be as obvious to exploit early on, but we can never underestimate market actors’ ability to source opportunities for additional revenue.

MEV creates incentives that encourage inefficiency

MEV encourages miners to further deviate from the time order of transactions in favour of ordering by transactions that generate income for the miner or miner-associated parties. The MEV income can drive centralisation around certain miners who would act like middlemen selling block construction as a product in a secondary market.

While miners would focus on their incentives to cover operating costs and drive profit, for the ordinary user and the network as a whole, it might cause trouble. As miners focus on MEV blocks, they disregard standard transactions, which could frustrate users as their transactions remain in the mempool longer than normal or require higher fees to be included in the next block.

Are you investing in the Bitcoin ecosystem?

Do you invest in bitcoin mining? Are you considering bitcoin mining? Have you been mining for some time? How do you deal with the noise? Let us know in the comments down below.