Humans are creatures of habit, and it’s remarkable how easily we can adapt to changes as long as we can carry on with the general trend we deem “normal” or accepted by society. Inflation is a natural occurrence in all forms of money we’ve had in the past; the only difference was the method and cost to add additional inflation to the money supply. Gold and silver have traditionally had inflation; you did have to do a lot of damn work that got consistently harder to extract it from the ground but still adds to the money supply.

If the ability to acquire a new money supply is more challenging than producing goods and services that will turn over the old money supply, we tend to deflate. Goods and services are more abundant than money, and prices tend to fall to extract the money out of those stubborn coffers.

Sure this is a bit of an oversimplification, but you get the gist of it. This concept of price deflation due to money supply constraints sounds plausible but is entirely foreign to most of us. We’ve long since left a hard money standard, and now currency issuers can create a new supply whenever it is “needed”.

The fiat fiend

The idea behind this cash injection is that you’re pushing new money into the economy to get productivity going. Once it’s ramped up, it will outproduce the new injection of cash over time, and we’d be back where we were minus the pain of an economic downturn. This is the theory or rather narrative we’ve been feed since 1971.

Like any drug or stimulant, the economy feels strong effects from micro-dosing here and there. Then the effects wear off, and we’re afraid of hitting those lows, so we up the dosage, and before you know it, you can’t remember the time you functioned without it.

Bringing it back home

Now I didn’t understand the games played with money; I still don’t understand most of it. Even though I try to keep up with it as the more financialised the economy, the more what they do carries weight in the productive economy where I find myself. For someone like me who works for a living, all the signal I get is that prices for the things I need to live keep going up.

I am sure you’ve had this conversation with friends and family, as you all provide various evidence of shopping behaviour changes. You would talk about

- Where to find the best discount

- What brands you can switch to that are cheaper without affecting your joy from the product too much.

- Collecting coupons and vouchers

- Travelling collectively where possible

- Tips on reducing consumption where possible

- How to save more money

- How to find a better return on your savings

All these conversions are centred around how to reduce the effects of inflation. Companies don’t go into business to make goods more expensive; in fact, their purpose is to see an underserviced gap in the market, where they can offer something cheaper.

Entrepreneurs do their best to find new ways to produce more goods or services at a cheaper rate so that they can attract more of the capital to their business instead of competitors.

So if business owners are actively trying to drive down prices, why do the items I want to buy become more expensive with time?

Most of us dismiss the nature of life becoming more expensive as part of the process but dismissing it will expose you to its sinister effects. Sadly human capital cannot be scaled exponentially; your labour can only acquire so much money, sooner or later, your wages erode via inflation.

Inflation, deflation debate

From conversations I’ve had with those living in developed markets, it’s a bit more opaque since they have the stronger currency they benefit from imports from other regions. These relationships can help offshore inflation. While some goods are cheaper, others are more expensive, giving you a mixed basket and creating all these debates on is a market inflationary or deflationary.

For someone like me in the developing world, it’s a lot easier to understand. ALL goods are constantly going up in price, regardless of production improvements, because of the increased supply of the currency.

Money is not productivity; it’s a measurement tool.

Money is without a doubt one of the most important tools we have today; it allows us to transact with one another. Money is nothing more than a claim on the productive goods of society. If there aren’t any goods or services, money means nothing.

If you’re starving but have money, you’ll be willing to pay any price for food, so if we keep adjusting the number of claims to goods and goods that take energy, labour and time to produce where money does not. It would only mean that the price for something harder to make would go up in value.

The person who spends their energy, labour, machinery, transportation costs and mental capacity would want some form of compensation they can use on a claim for someone else productivity later. So the harder something is to produce, the more it will require compensation to acquire.

Sure we place a lot of emphasis on money in our modern society, so it makes it hard to understand that these claims are constantly exceeding the number of goods and services it can lay claim to, but this is currency inflation. We are experiencing its effects first hand.

The South African Rand

The Rand launched on 14 February 1961, as part of South Africa’s independence from Britain; before that, the nation’s currency was the British pound.

So how has the Rand faired over its 60-year life span? The average annual inflation rate has been 7.85% meaning the Rand has inflated by 9,219.25%.

According to inflationtool.com, R1 in 1961 would have the purchasing power of R93.28 in 2021.

I don’t think you need more than basic arithmetic to understand that anyone who is saving in Rands gets a raw deal, if the annual inflation rate over its life span is 7.85% how many investments can kick off an 8% return to clear that hurdle rate? Not many I would assume.

What is the M2 Money supply?

The M2 money supply refers to the total volume of money held by the public at a particular time in an economy. There are several ways to define “money”, but standard measures usually include currency in circulation and demand deposits.

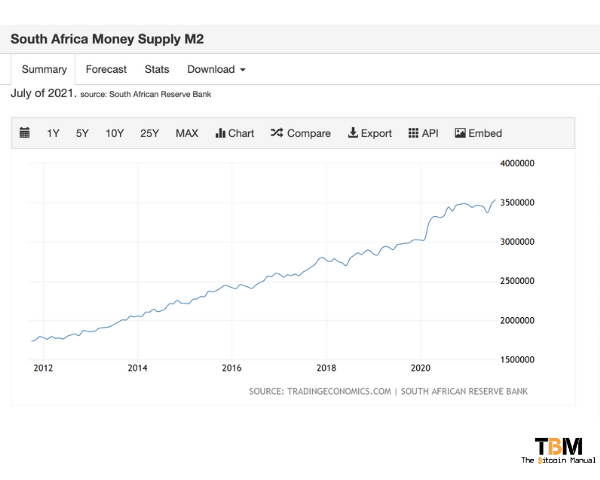

If we look at the M2 money supply in South Africa, it’s pretty much sitting at its all-time high in nominal units.

If we look at the M2 money supply growth according to tradingeconomics.com over the last ten years in South Africa, the time I’ve been in the workforce, it’s grown by double in that time from 1.7 trillion South African Rands to around 3.5 trillion South African Rands.

Now the unit amount sounds minuscule compared to the number of units in the US. Still, we have to remember it’s not about units; it’s about claims on total productivity, of which South Africa has a far smaller productivity output than the US.

An example of inflation at play in South Africa.

According to business tech, the price of an average basket of consumer food products has gone up by 22% annually. Now, apart from the maize and cabbage example, very few South African’s receive an increase in salary that can outpace those increases.

| Product | Description | 2017 | 2021 |

| Apples | 1.5 Kg | 0.00008340 | 0.00006541 |

| Bread | Brown, one loaf | 0.00003753 | 0,00002440 |

| Cabbage | One head | 0.00005817 | 0.00003384 |

| Coca Cola | 2 litres | 0.00006252 | 0.00005193 |

| Eggs | 6 extra-large | 0.00006982 | 0.00004619 |

| Flour | Self-raising 2.5 kg | 0.00014200 | 0.00009813 |

| Maize | 2.5 kg | 0.00009889 | 0.00006082 |

| Margarine | 500g | 0.00009310 | 0.00006082 |

| Milk | full cream, 2 litres | 0.00009791 | 0.00007402 |

| Rice | 2 Kg | 0.00009986 | 0.00007000 |

| Sugar | White, 2.5 Kg | 0.00014643 | 0.00010501 |

| Tea | 100 bags | 0.00007995 | 0.00007459 |

| Total | Value of total goods | 0.00106958 | 0.00076918 |

Note:

To try and be as fair as possible, I will be comparing the highest Bitcoin price of 2017 to the lowest Bitcoin dropped in 2021

- Highest Bitcoin price in 2017 – ZAR 257 660

- Lowest Bitcoin price in 2021 – ZAR 435 538

When priced in Bitcoin the goods that were 22% more expensive after 5 years are now -28.09% cheaper than they were 5 years ago.

The Bitcoin flipping.

Once the M2 money supply clicked for me, there was no going back; I was in shock. I felt robbed, watching all I’ve worked so hard for completely melt in front of me without any way to protect against it. I was angry; I felt like you were only delaying the inevitable.

I, like many South African’s, are stuck making the decision, do we take the brunt of the inflation, or do we head further out the risk curve with the potential to lose it all but try to outpace it or rather, lose less than others.

Bitcoin was one of those shots in the dark; when I bought it back in 2015, I didn’t realise what I was bought, and it took me six years to figure it out. Sure, the NGU (Number Go Up) technology got me into Bitcoin, as it was the only thing outpacing the growth of the money supply. Still, it also opened my eyes to concepts like saving, low time preference, risk-adjusted returns, discounted cash flow and a host of other ideas that I feel have made me a better saver.

I wouldn’t say I am an investor; investors take on risk; I am just an avid saver that found a method of saving that works. I like to save; I was saving via the incorrect medium and getting punished via inflation.

With Bitcoin, Instead of being a victim of inflation, I am now a beneficiary of this trend. When I purchased Bitcoin, I lock today’s productivity into its time chain, and I can preserve it in the long term. I feel confident that very few people will have the chance to acquire the same amount of satoshis at the value I purchased it at in the future.

When are you going to cash in?

I’ve also been asked when will I “cash out” as if Bitcoin are some casino chips, and I’ve been winning at the tables all night. I speak to friends in developed nations, and they’re always talking about a particular USD value, EUR or GBP value where they can cash in their Bitcoin and run off to the Maldives. I get it; your currency has some relative importance, you can do something with it.

I, on the other hand, have no ambition to convert back into South African Rands.

If you had US dollars in Venezuela or Zimbabwe, would you be looking to cash it in for Venezealun Bolivar or Zimbabwean Dollars because the unit price is now higher? No, the confidence in that currency is long gone, and you wouldn’t touch it as a sane economic actor.

I am simply acting as rational as I can; I have no confidence in my local currency, and why should I? Have they given me ANY indication they can turn it around? No.

I now have a currency valued the world over at the same purchasing power, and I am not willing to let that go.

The price of tomorrow.

To steal the title of Jeff Booth’s book, which I highly recommend your read, the price of tomorrow is up to your unit of account. If your unit of account is South African rands, you’ll have to constantly acquire more units to give out more units to acquire goods and services.

If you’re like me and your unit of account is satoshis, you don’t have to acquire more satoshis, but you want to. The satoshis you have acquired are engineered to acquire more goods and services.

Remember earlier I spoke about the cost of production? Well, Bitcoins cost to produce, and insurance becomes harder with time; the harder it becomes, the easier other things are produced for the same cost. This process playing out makes everything compared to a satoshi cheaper with time.

Instead of looking at how many sats a dollar gets you or whatever fiat currency you are stuck with, look at how many sats to acquire a home or a business. You’ll see that unit value continues to shrink with time, and you will be able to avoid those large ticket purchases when saving with Bitcoin should the trend persist.

2 Responses

Nice article! Super interesting and eye-opening. Particularly relevant to all South Africans.

Thanks, Josh, we appreciate it, I think everyone will find a way to Bitcoin differently and framing ideas that people understand is the best way to get them involved