Bitcoin is considered an open monetary network due to two key features: decentralisation of access to the network, since anyone can run a node or miner and support or use the network, and the entire system resting on an open-source code base that anyone can review and run. Unlike traditional currencies controlled by governments or banks, Bitcoin operates on a peer-to-peer network with nodes and miners distributed globally.

There is no central authority managing transactions, which are verified and secured by a distributed network of computers. This transparency requires no trust in a central authority as the source of truth and allows anyone to verify the data in the network.

Combining all these traits creates an open system for transferring and holding value independent of any central control; value transfer is censorship-resistant and hard to seize, and those properties can be used to transfer the proceeds of crime.

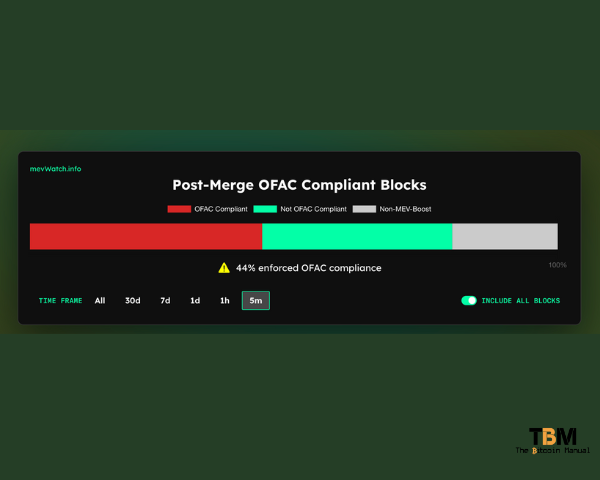

We’ve already seen networks like Ethereum baulk under OFAC regulations, with the majority of validators excluding transactions that would violate these government lists, and while blacklisting of Ethereum addresses connected to the Tornado Cash mixing service raises uneasy questions about Bitcoin’s ability to resist government pressures.

With more money flowing into the Bitcoin ecosystem, governments are looking for ways to exert pressure on the Bitcoin network under the guise of consumer protection and national security.

What is OFAC compliance?

OFAC compliance refers to adhering to the regulations set by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), a department of the US Treasury. OFAC’s primary function is to enforce economic and trade sanctions imposed by the US on specific countries, individuals, and organisations.

These sanctions are implemented to achieve foreign policy and national security objectives

- Who Needs to Comply:

- All US persons (citizens and permanent residents anywhere in the world)

- Entities within the US

- US-incorporated entities and their foreign branches (in some cases)

- Foreign subsidiaries of US companies (depending on the sanction program)

- In certain situations, foreign persons dealing with US-origin goods

- What it Means to Comply: Generally, OFAC compliance boils down to avoiding prohibited transactions with sanctioned parties. This includes:

- Blocking assets owned by sanctioned entities

- Trade restrictions on goods and services

- Sanctions Compliance Programs: While not mandatory, OFAC expects companies engaging in certain activities to have a sanctions compliance program in place. This is particularly important for businesses that:

- Conduct a high volume of international transactions

- Deal with customers in high-risk regions

- Have a large and frequently changing customer base

- Consequences of Non-Compliance: Violating OFAC regulations can lead to severe penalties, including hefty fines and even criminal charges.

The fact that there are bitcoin addresses on the OFAC sanctions list is ridiculous…

— Jameson Lopp (@lopp) November 22, 2023

Because YOU'RE NOT SUPPOSED TO RE-USE BITCOIN ADDRESSES.

Who are the baddies?

The OFAC list, specifically the Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons List (SDN), includes individuals and entities the US government has sanctioned. OFAC sanctions can be targeted or broad-based, with targeted sanctions focusing on specific individuals and entities, while broad-based sanctions apply to entire countries.

- Individuals: Terrorists, narcotics traffickers, arms dealers, and other individuals engaging in activities the US deems a threat.

- Companies: Businesses owned or controlled by sanctioned countries or individuals.

- Foreign governments: Entire countries on which the US has imposed sanctions.

- Organisations: Groups involved in the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, human rights abuses, or other activities targeted by US sanctions.

Miners are already seen as a target for regulators

Large Bitcoin miners in the US are an easy target; they’ve already committed capital to a particular location and co-located with an energy source, making compliance easier than picking up and moving elsewhere. Some private companies might want to become publicly listed companies, so they must play nice with regulators and governments.

Meanwhile, publicly listed miners committed themselves to regulatory scrutiny and pressure for US OFAC compliance when they filed their S1.

Carole House tells congress that bitcoin miners should enforce OFAC sanctions at the network level 🚩🚩 pic.twitter.com/QSBKQCic9D

— Pledditor (@Pledditor) February 15, 2024

In May 2021, Marathon Digital Holdings, a U.S.-based bitcoin mining firm, said it would exclude from the blocks it mined any transactions involving addresses sanctioned by the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

Regulators can target miners, asking them to avoid processing and completing blocks checked against OFAC-flagged addresses. Bitcoin miners do come in all sizes, from the garage miner running an ASIC at home all the way up to these large data centres.

As long as a miner is seeking a profit, a block producer somewhere in the world will include your transaction in a block; this could be an individual or an entity in another country. Well, that’s how the theory goes, but many individual miners point their hash rate to KYC mining pools registered in the US, which could also be subject to the same pressure as public miners.

As the rules around block composition become stricter, hashers seeking out the most profitable transactions will need to consider pointing their hash rate to mining pools that don’t KYC and allow miners to compile their own blocks.

Lightning isn’t going to be a free ride

Lightspark is an LSP and Lighting infrastructure company that works with exchanges and businesses to add support for Bitcoin payments via on-chain and on lightning; one of its premier products is UMA, a fork of Lightning Addresses which can be used to implement compliance features such as KYC/AML checks and sanctions screening of Bitcoin payments.

"Lightspark conducts screenings for US economic sanctions for jurisdictions subject to comprehensive US sanctions by OFAC."

— Nikita Zhavoronkov (@nikzh) April 3, 2024

Get your KYC documents ready and welcome to the future of Bitcoin payments! ⚡️

Lightning is not Bitcoin, it's a scam. https://t.co/Chj5R8qJ2s

Amboss, a Lightning-focused company with a liquidity market Lighting data provider, recently released its own compliance tool, Reflex. This tool censors transactions based on the IP address of the Lightning node and allows businesses to screen nodes for OFAC compliance.

Let‘s talk about @ambosstech‘s new product „Reflex“ and why you should close all channels to Amboss immediately.

— L0la L33tz (@L0laL33tz) April 4, 2024

Reflex is a product bringing OFAC compliance to LN Nodes, yet the product is advertised as increasing „Freedom“ for node runners – and freedom, according to Amboss,… pic.twitter.com/6yT984A37B

Two Lightning companies only make up part of the network.

Lightning remains a peer-opt network, with any user having the option to choose which nodes to interact with. As long as routing between nodes remains open, your payments on the network will continue to settle, regardless of what OFAC-compliant nodes are doing in their corner of the network.

The one concern is that the number of users who are using custodial Lightning might see their LSPs fall in line or get shut down, which could force users into migrating to non-custodial options.

Node operators with current clear net Lightning nodes might also opt for a Tor node instead as their default, which might be a little laggy, but privacy will always come at a cost.

CoinJoins have also seen an OFAC creep

If you have tainted coins, one way to circumvent the on-chain tracking heuristics is to mix your coins with other users through CoinJoins. Think of it as a massive pot of coins, where users will all place, shake it all up, and pull out a Bitcoin.

While you still have the same amount of funds, the origin of those funds is now obscured, and those tracking your coins cannot make the same assumptions about who owns those UTXOs now. If you want to participate in a CoinJoin, you can run the protocol yourself or use a coordinating service like Wasabi or Samouri Wallet.

Unfortunately, regulators can target these on-ramps, and we’ve already seen some OFAC compliance begin to sneak into this privacy practice.

In March 2022, zkSNACKs, the company behind the Wasabi wallet, a privacy-focused mixing wallet, stated that it would screen coins that could be added to its service and match them with an OFAC list.

According to a tweet under the Wasabi Wallet Twitter handle, the screening process will bar certain bitcoin (BTC) transactions from its service, which facilitates privacy-enhancing transactions known as CoinJoins.

The zkSNACKs coordinator will start refusing certain UTXOs from registering to coinjoins. pic.twitter.com/X3kBuQwieO

— Wasabi Wallet (@wasabiwallet) March 13, 2022

CoinJoin is an open-source protocol, so restrictions imposed by one service provider do not end these group transactions and Bitcoin privacy. If you’re worried your coins won’t make it to a Wastabi white list, you could run a Join Market like Jam on your node and pay others to mix with your coins.

Improving Bitcoin privacy

The issue with CoinJoins is that governments can easily apply a blanket rule that any mixer outputs are now tainted to discourage users and businesses from mixing. Since mixing history remains with those UTXO, it becomes a tough decision for someone who wants more privacy.

Bitcoin’s Taproot upgrade in November 2021 introduced features that would make coin-mixing transactions less obvious to anyone trying to filter them out.

Schnorr Signatures

Schnorr signatures are a simpler and more efficient alternative to the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) signatures commonly used today. Schnorr signatures allow users to combine their signatures so that only one aggregated signature is used. From a privacy perspective, multiple signers make it difficult to determine each signer’s identity accurately.

MuSig2

Another benefit of Schnorr signatures is combining multiple public Bitcoin addresses (public keys) into a single address using a signature scheme called MuSig2. When bitcoin is sent to these composite MuSig2 addresses, it resembles standard bitcoin transactions rather than multi-sig transactions.

MAST

The Taproot upgrade also integrated Merkelized Alternative Script Trees (MAST). MAST integration reduces transaction size and increases transaction privacy by concealing transaction spending conditions. MAST allows for better privacy by combining and hashing these spending instructions.

Cross-input signature aggregation (CISA)

Cross-input signature aggregation is an exciting Bitcoin enhancement that hasn’t been implemented yet but is in the works. CISA would allow multiple inputs in a Bitcoin transaction to share a single signature, making mixing activities like CoinJoins and PayJoins cheaper.

Using CISA, the fees for a CoinJoin are the same as those for a single transaction. The hope is that this will encourage more users to use UTXO mixing transactions and increase the size of the CoinJoin group.

Tainted coins don’t stay tainted forever

A UTXO’s status as tainted begins and ends with the government’s decision. Eventually, if enough time has passed, seized coins can be “untained” and returned to the open market.

We were reminded of this fact recently; in April of 2022, a wallet tagged as belonging to the U.S. government moved 30,175 Bitcoin to CoinBase, which would roughly net them around $2 billion at current prices.

The last confirmed sale by the U.S. government was in March 2023, when it unloaded 9,861 coins for $216 million as it continued to sell off the total 50,000 BTC seized from the Silk Road.